Implicit Membrane REMD Structures of Full-length C99 protein

I briefly discuss preparation of full-length C99 simulations in GBSW implicit membranes using REMD and provide prepresentative structures from clustering.

C99, a 99-residue long C-terminus of Amyloid Precursor Protein, is the precursor to amyoid beta A\(\beta\).

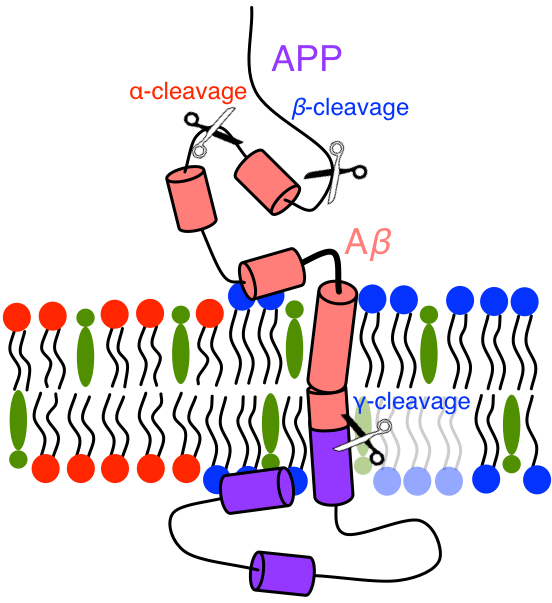

Amyloid precursor protein (APP) is a (canonically) 770-residue long protein central to the amyloid cascade hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).[1] APP is cleaved by either \(\alpha\)- or \(\beta\)-secretase outside of cellular membranes, primarily producing 83- or 99-residue long C-terminal fragments known as C83 or C99. In the amyloid cascade, C99 is then cleaved by \(\gamma\)-secretase in its transmembrane region, resulting in one of many possible lengths of \(A\beta\) (primarily 38, 40, 42, 43), which can be selected by changing the structural ensemble of C99 and thus the point of cleavage on C99 by \(\gamma\)-secretase. It is these longer fragments, \(A\beta_{42}\) and \(A\beta_{43}\), which form oligomers, fibrils, and tangles which are implicated in AD.

Figure: Cartoon of C-terminal region of APP. Scissors show the approximate locations of \(\alpha\)-, \(\beta\)-, and \(\gamma\)-secretase cleavage sites on APP. In membranes of sufficient cholesterol concentration lipid raft domains form, rich in saturated lipid and cholesterol, to which APPs partition. In raft domains APP colocalizes with \(\beta\)-secretase and C99 with \(\gamma\)-secretase. At low cholesterol concentrations APP will colocalize with \(\alpha\)-secretase, avoiding the amyloid cascade.

There are many important mutations that have been identified in the brains of AD patients which appear in the extra-membrane N- and C-terminal domains of C99. Additionally, the N-terminus of C99 is likely critical to C99-\(\gamma\)-secretase binding and the C-terminus of C99 is involved in interactions with many cytoplasmic proteins. Part of the N- and C-terminal domains of C99 have been evidenced to be intrinsically disordered, and thus the structural ensemble of C99 in these domains had not been resolved. The body of work resolving part of the N- and C-terminal structure of C99 and the key residues present in these termini were summarized in our recent publication in Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. In addition to this, we summarized the body of work that has formed our understanding of membrane environment effects on the C99 transmembrane domain structural ensmeble.

Preparation of the full-length C99 protein from experimental data.

Though the transmembrane domain of C99 has an NMR-resolved structure (PDB: 2LP1),[2] the full-length structure of C99 has not been resolved via experimenal methods. However, there are backbone chemical shift assignments for the majority of the C99 sequence, determined via solution NMR in LMPG micelles by Sanders and coworkers (BMRB: 15775).[3]

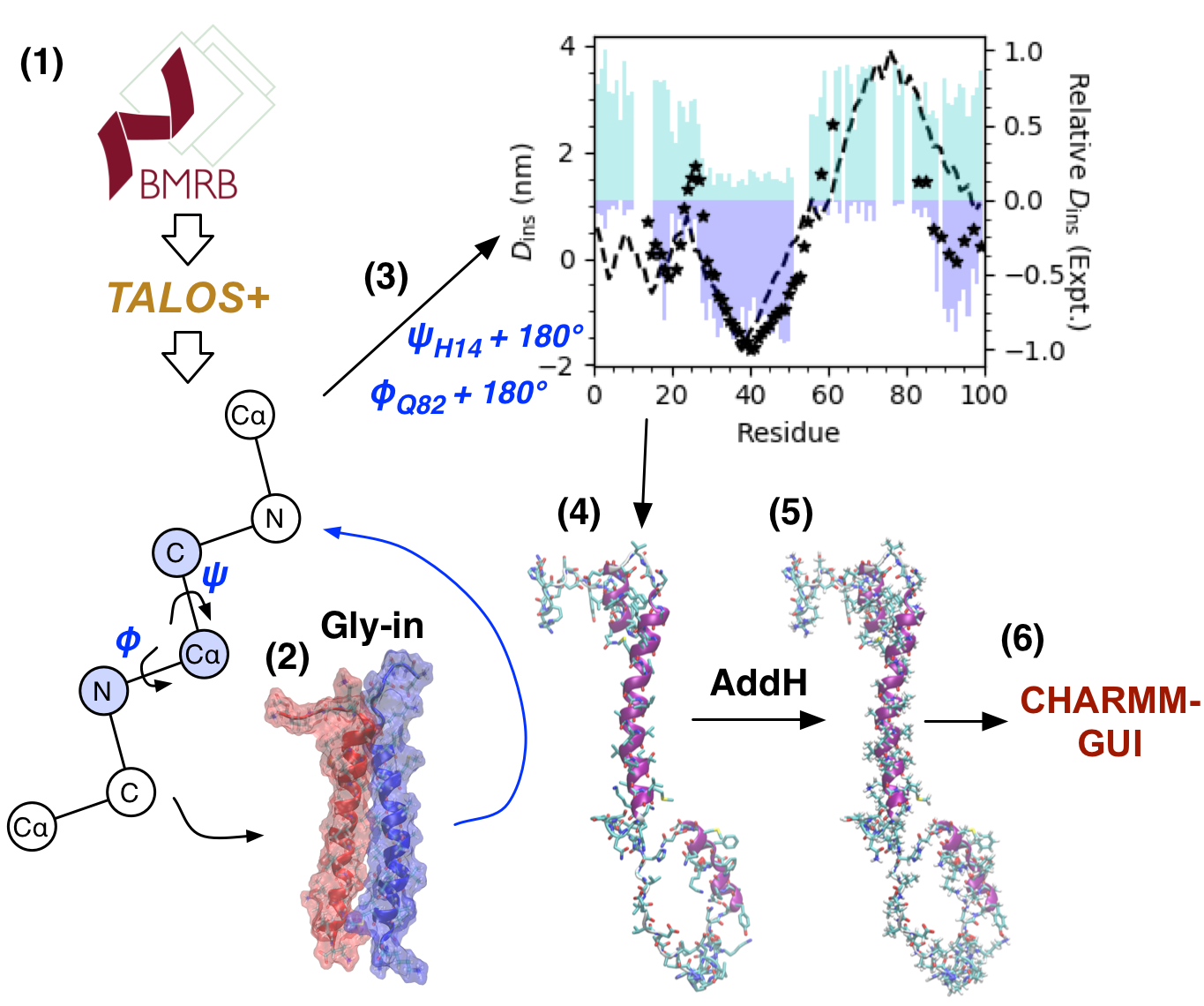

We modelled the initial structure of C99 via a combination of structure from simulation and backbone chemical shifts (13C, 15N, 1H) using (1) TALOS+, an emperical method for assigning dihedral angles from backbone chemical shifts. (2) Re-assignment of the transmembrane domain (residues 23-55) dihedral angles to those observed in the “Gly-in” structure of C99 homodimers.[4] (3) Changing the \(\psi\) angle of H14 and the \(\phi\) angle Q82 both by 180° in order to recover more accurate insertion depths of C99 residues, compared to past experimental measurements in bilayers and bicelles. (4) Assignment of rotomeric states of sidechains via the rotamer library of Shapovalov and Dunbrack. (5) Assignment of pH 7 protonation states using the AddH program in UCSF Chimera. (6) Atom renaming for CHARMM format, addition of caps to N- and C-termini, and generation of PSF file using CHARMM-GUI.

Figure: The process used to construct the initial state of full-length C99. (1) TALOS+ predicts dihedral from backbone NMR, (2) transmembrane domain dihedrals reaassigned based on “Gly-in” motif, (3) H14 \(\psi\) and Q82 \(\phi\) rotated 180° to get better agreement with EPR (stars) and NMR (cyan hydrophilic probe signal; blue hydrophobic probe signal), proposed structure insertion in dashed lines, (4) rotamer assignment, (5) protonation state assignment, and (6) atom renaming, terminal capping, and PSF file generation.

GBSW Implicit Membrane and REMD simulation.

Given the complexity and length of the extra-membrane domains of C99 we initiated studies of the full-length sequence of C99 using the Generalized Born with a simple SWitching (GBSW)[5] implicit membrane model and replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD).[6] I may provide a brief explanation of GBSW in the future. I wrote a brief explanation of REMD in a previous post.

A Temperature REMD tutorial using REPDSTR in CHARMM has previously been written on charmmtutorial.org by Tim Miller. A GBSW membrane tutorial has been written by Wonpil Im and Jianhan Chen on mmtsb.org.

Representative structures from GBSW REMD simulation determined using C\(\alpha\) and dihedral PCA of N- and C-terminal domains.

To precicely form clusters of C99 structures sampled at 310 K in these 30-, 35-, and 40-Å thick membranes over 130, 160, and 460 ns REMD simulations, we performed PCA of combined C\(\alpha\) and dihedral angle data across all ensembles of N- and C-terminal domains (separately), using the three largest eigenmodes of each PCA to obtain a 12-dimensional space in which conformational clustering of principal components was performed using gaussian mixture models.

For the benefit of other researchers, I’ve uploaded the final structure assigned to each of the 16 conformational cluster in these 30-, 35-, and 40-Å thick membranes to my github, including all PSF files generated by CHARMM-GUI.

For more details on our work, please read our manuscript: G.A. Pantelopulos, J.E. Straub, D. Thirumalai, & Y. Sugita “Structure of APP-C991–99 and implications for role of extra-membrane domains in function and oligomerization,” BBA Biomembr. (2018) doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.04.002

References:

- J.A. Hardy & G.A. Higgins, “Alzhimer’s Disease: The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis,” Science 256 184-185 (1992).

- P.J. Barrett, Y. Song, W.D. Van Horn, E.J. Hustedt, J.M. Schafer, A. Hadziselimovic, A.J. Beel, C.R. Sanders, “The Amyloid Precursor Protein Has a Flexible Transmembrane Domain and Binds Cholesterol,” Science 336 1168-1171 (2012)

- A. Beel, C. Mobley, H. Kim, F. Tian, A. Hadziselimovic, B. Jap, J. Prestegard, & C. Sanders, “Structural Studies of the Transmembrane C-Terminal Domain of the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP): Does APP Function as a Cholesterol Sensor?,” Biochemistry 47, 9428-9446 (2008).

- L. Dominguez, L. Foster, J.E. Straub, & Thirumalai, “Impact of membrane lipid composition on the structure and stability of the transmembrane domain of amyloid precursor protein,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113 E5281–E5287 (2016).

- W. Im, M. Feig, & C.L. Brooks, “An Implicit Membrane Generalized Born Theory for the Study of Structure, Stability, and Interactions of Membrane Proteins,” Biophys. J. 85 2900–2918 (2003).

- Y. Sugita, & Y. Okamoto, “Replica exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding simulation,” Chem. Phys. Lett. 314 141–151 (1999).