Mass-Scaling Simulated Tempering for Optimizing Time-steps

The simulated and parallel tempering are briefly discussed. I explain the MSST method and present its implementation in OpenMM.

Tempering

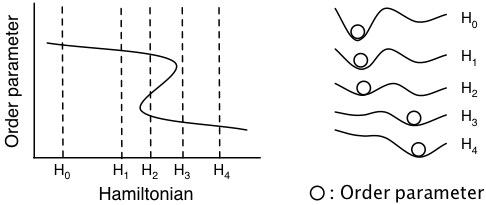

Sampling of the equilibrium state of a system with Hamiltonian Hi can be hampered by barriers in the system free energy landscape. These barriers can be more easily crossed without prior knowledge of the free energy landscape via tempering the Hamiltonian.

Figure: The system order parameter at various realizations of a the Hamiltonian.

The Hamiltonian is most commonly tempered by raising the system temperature (as the name implies).

Parallel Tempering aka Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD)

With no prior knowledge of the system, parallel tempering with temperature is a simplistic method to quickly sample the equilibrium state of a Hamiltonian Hi.

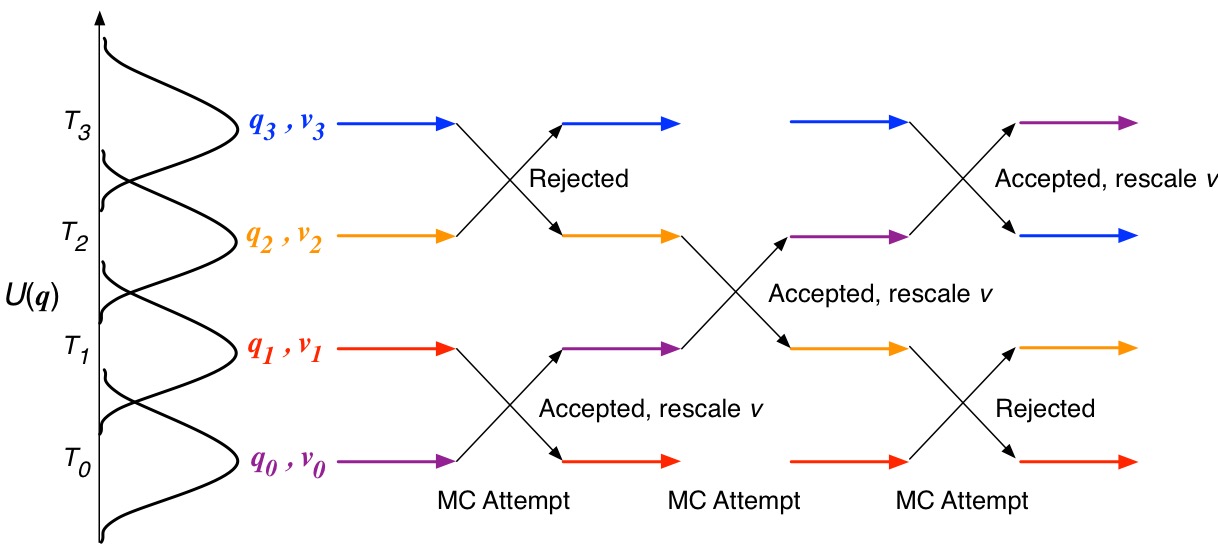

Typically, MD trajectories in each Hamiltonian are run in parallel and periodically swap temperature following the Metropolis-Hastings criterion.

\[p = \text{min}\left(1,e^{(U_i - U_j)(\frac{1}{k_\text{B}T_i} - \frac{1}{k_\text{B}T_j}) }\right)\]After successful temperature exchange, velocities are rescaled for what we should expect in the new temperature condition.

\[v_i = v_i \sqrt{\frac{T_j}{T_i}},\quad v_j = v_j \sqrt{\frac{T_i}{T_j}}\]The most typical method to attempt to exchange i and j simulation conditions is to alternatively select even and odd-numbered pairs of most-similar (neighboring) simulation conditions.

Figure: Illustration of REMD with temperature replicas using even-odd pair neighbor swapping.

Simulated Tempering (ST)

Running parallel trajectories can be extremely expensive, so much so that the computational efficiency of sampling might be less than that of a typical MD simulation.

Simulated Tempering (ST) employs a single trajectory with a temperature exchange criterion intended to achieve a random walk in temperature, requiring knowledge of the free energy landscape. MC swaps are similar to parallel tempering:

\[p = \text{min}\left(1,e^{(\frac{1}{k_\text{B}T_i} - \frac{1}{k_\text{B}T_j})U_i + g(T_i) - g(T_j)}\right)\]Where g(T) is parameterized to both achieve a random walk in temperature space and preserve balance. Velocities are also rescaled, as in REMD:

\[v' = v \sqrt{\frac{T_j}{T_i}}\]g(T) is most commonly determined by:

- Sufficient sampling with parallel tempering to estimate a(T) via WHAM or MBAR

- On the fly using the Wang-Landau algorithm

OpenMM provides a very simple environment for writing efficient GPU-accelerated MD simulations. GPU acceleration can enormously increase the computational efficiency of ST relative to REMD!

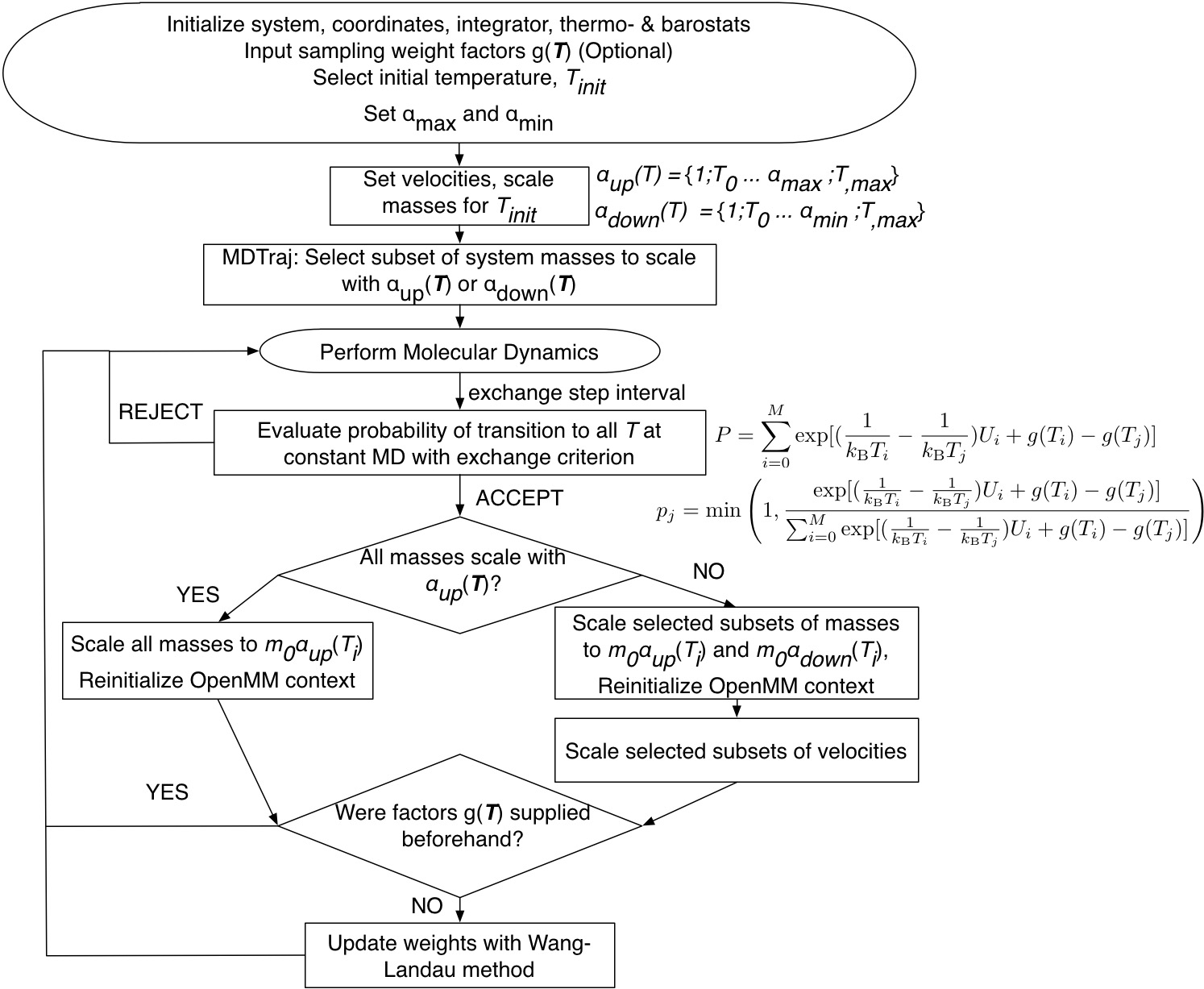

Mass-Scaling Simulated Tempering (MSST)

Molecular motion at high temperatures employed in tempering can require the use of small time-steps to avoid accumulative errors in kinetic energy. Time-step sizes can be scaled with temperature, but this is a needless cost.

By manipulating the masses of all atoms in the system as dependent on temperature we can utilize one optimal time-step and which does not require velocity scaling!

We may make all masses scale as \(m_k(T_i) = m_{0,k}\frac{T_i}{T_0}\) where \(m_0\) are the masses at initial the lowest temperature \(T_0\).

As such, we have the kinetic energy: \(K_i(v) = \sum^N_{k = 1}\frac{m_{0,k} \frac{T_i}{T_0}\mathbf{v}_k^2}{2}\)

And the ensemble weight factor: \(w(q,v,T_i) = e^{-K_i(v)-U(q)/k_\text{B}T_i + g(T_i)} = \\ \text{exp} [{\sum^N_{k = 1}\frac{m_{0,k} \frac{T_i}{T_0}\mathbf{v}_k^2}{2 k_\text{B} T_i}-(U(q)/k_\text{B}T_i) + g(T_i)}]\)

in which we see that the velocity distributions are independent of temperature!

Additionally, rather than scaling all masses in the system, a subset of the system may be mass-scaled by some arbitrary amount \(\alpha\), such that \(m_k(T_i) = \alpha_{k,i} m_{0,k}\frac{T_i}{T_0}\) and velocities will then be re-scaled upon changing temperature as \(v_k' = \sqrt{\frac{\alpha_{k,i}}{\alpha_{k,j}}} \sqrt{\frac{T_j}{T_i}} v_k\).

Doing this of course causes the loss of the special ability to find one optimal time-step for the simulation, but it can help reduce errors in integration. Additionally, the scaling of separate groups of atoms, such as protein hydrogens and sidechains to decrease viscosity, has been used to enhance sampling in protein simulations.[1]

In a 2016 paper,[2] we performed MSST simulations of LJ fluid, coarse-grained lipid simulation, and atomistic Trp-cage folding, demonstrating the ability to use longer time-steps and reduce integration errors.

Below is detailed the MSST implementation workflow in OpenMM, for which there is an example application with Trp-cage folding following the classic protein folding paper by Simmerling et. al.[3] on my github. This is a “hack” of OpenMM head developer Peter Eastman’s simulatedtempering.py.

Figure: Workflow for the MSST implementation in OpenMM.

The MSST method, or its accompanying Mass-Scaling Replica Exchange Method,[4,5] may be used to lengthen the time-step of simulations employing tempering. In most cases the change to velocities will often not matter as tempering simulations are conducted to measure ensemble-averaged structural proterties, only dependent on \(U(\mathbf{q})\).

Please read and cite:

T. Nagai, G.A. Pantelopulos, T. Takahashi, & J.E. Straub “On the use of mass scaling for stable and efficient simulated tempering with molecular dynamics,” J. Comp. Chem. 27 2017-2028 (2016).

References:

[1] Lin, I.-C. & Tuckerman, M. E. “Enhanced Conformational Sampling of Peptides via Reduced Side-Chain and Solvent Masses,” J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 15935–15940 (2010).

[2] T. Nagai, G.A. Pantelopulos, T. Takahashi, & J.E. Straub “On the use of mass scaling for stable and efficient simulated tempering with molecular dynamics,” J. Comp. Chem. 27 2017-2028 (2016).

[3] Simmerling, C., Strockbine, B. & Roitberg, A. E. “All-atom structure prediction and folding simulations of a stable protein,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 11258–11259 (2002).

[4] Nagai, T. & Takahashi, T. “Mass-scaling replica-exchange molecular dynamics optimizes computational resources with simpler algorithm,” J. Chem. Phys. 141, (2014).

[5] Nagai, T. “General Formalism of Mass Scaling Approach for Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics and its Application,” J. Phys. Soc. Japan 86, 14003 (2017).